This study was originally published on the Atlantic Council website.

On September 28, the Syrian government proposed the 2021 budget, planned at 8.5 trillion Syrian pounds ($2.7 billion in inflation-adjusted USD – hereafter referred to as “real terms”). The breakdown of the budget is still being debated in the People’s Council, the legislative branch of the Syrian government. Due to the sharp depreciation of the Syrian pound and the accelerated slowdown in economic activity over the course of the current year, the 2021 budget is not only a 27 percent decrease compared to last year in real terms, but is also the smallest budget since the uprising in 2011.

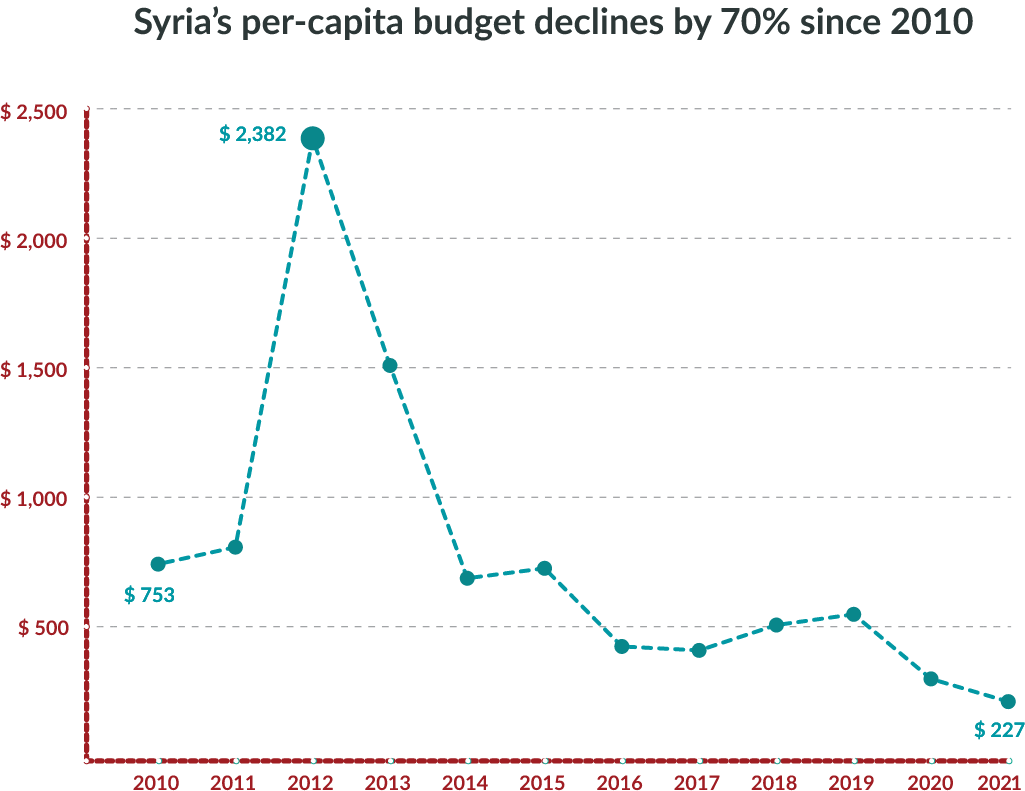

The latest contraction in Damascus’s spending is nothing new. Since 2010, our calculations show that Syria’s per capita budget spending has declined by 70 percent. Though it is well known that government spending has been shrinking in Syria since the uprising began, examining spending on a per-capita basis highlights the true severity of the country’s economic crisis. To put this in perspective, in 2021 the government will spend about one-third of the amount on its citizens that it did in 2010—despite the fact that there are only about half the number of people living under its control (11.7 million in 2020 versus 21.4 million in 2010).

For the data, calculations, and sources, click here.

Shrinking revenues, shrinking budgets

The continual decline in Syria’s budgetary spending reflects a shrinking revenue base upon which Damascus can draw. In 2021, total revenue is a whopping 83 percent lower than in the pre-war budget of 2010. Not only did the total revenue fall, but its composition has changed as well.

According to a report by the Syrian Center for Policy Research, in 2019 non-taxation-related income represented only a third of annual public revenue, due in large part to a 90 percent drop in oil production in regime-held areas since the start of the conflict (368,000 barrels per day in 2011 compared with 22,000 bpd in 2020). Comparatively, non-tax revenue constituted two-thirds of government revenues in the pre-war 2010 budget. How much the government can continue to squeeze out of people in taxes without stoking pre-existing grievances remains to be seen. Prior to the current economic crisis, over 80 percent of the population lived in “extreme poverty,” according to the United Nations in March 2019.

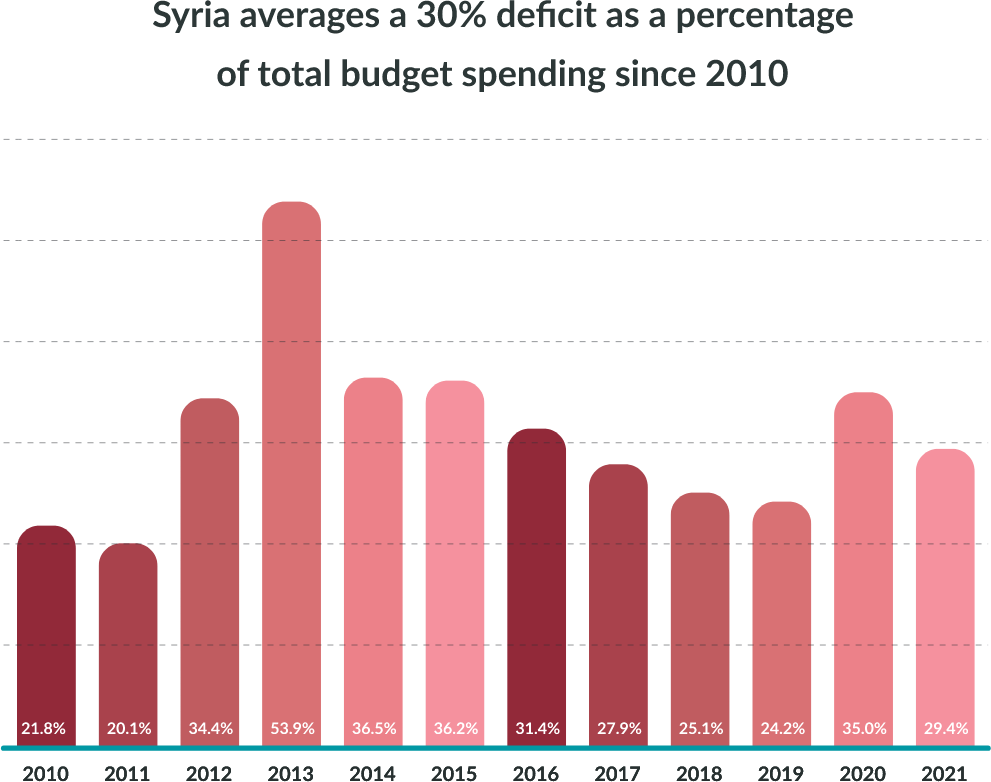

As the level of income declined considerably over the years of the conflict, taxation was not enough to fund all the Syrian government’s expenses, resulting in large and sustained deficits. The projected revenues for the 2021 budget currently sit at around 6 trillion Syrian pounds ($2.1 billion), creating a budget deficit of 2.5 trillion Syrian pounds ($902 million). Though Damascus is likely to have borrowed large sums from domestic and foreign actors since 2011, trying to judge precisely how “indebted” the government is impossible given the Syrian government’s opaque financial transactions.

In Syria, however, the budget deficits, largely classified as “taken from reserves,” do not reveal whether the amount is merely newly printed money, bonds issued, or money extended in the form of loans from the Central Bank. The significant increase in prices, especially since the recent deterioration in late 2019, suggests that much of the amount “taken from reserves” is newly printed money. Either way, whether what is being reported as taken from reserves is just new Syrian pounds or loans, there is no real incentive for the government to ever return money “borrowed” from state banks. While borrowing from the private sector in the form of bonds is a better alternative to printing money, as it keeps the lid on inflation, the appetite for lending to the Syrian state is weak and waning, forcing the state to pursue other lending avenues.

For the data, calculations, and sources, click here.

In addition to domestic debt, Syria has been loaned massive amounts of money from foreign governments, mainly Iran. Though there are no reliable figures as to the amount, some analysts have suggested that Iran has lent Syria between $30 and $105 billion throughout the war—more than ten times Syria’s 2021 budget relative to the lower estimate. Much of Iran’s debt to Syria is extended under the guise of a rather mysterious “credit line.” Russia’s support for the Syrian regime, on the other hand, is largely political and military.

It’s not possible for Damascus to begin to think about paying back its international creditors under the current circumstances. As for its domestically-held debt extended by the private sector, Damascus will likely print yet more pounds to pay it off, further exacerbating the extreme inflation levels that the currency experienced this year.

Say goodbye to reconstruction

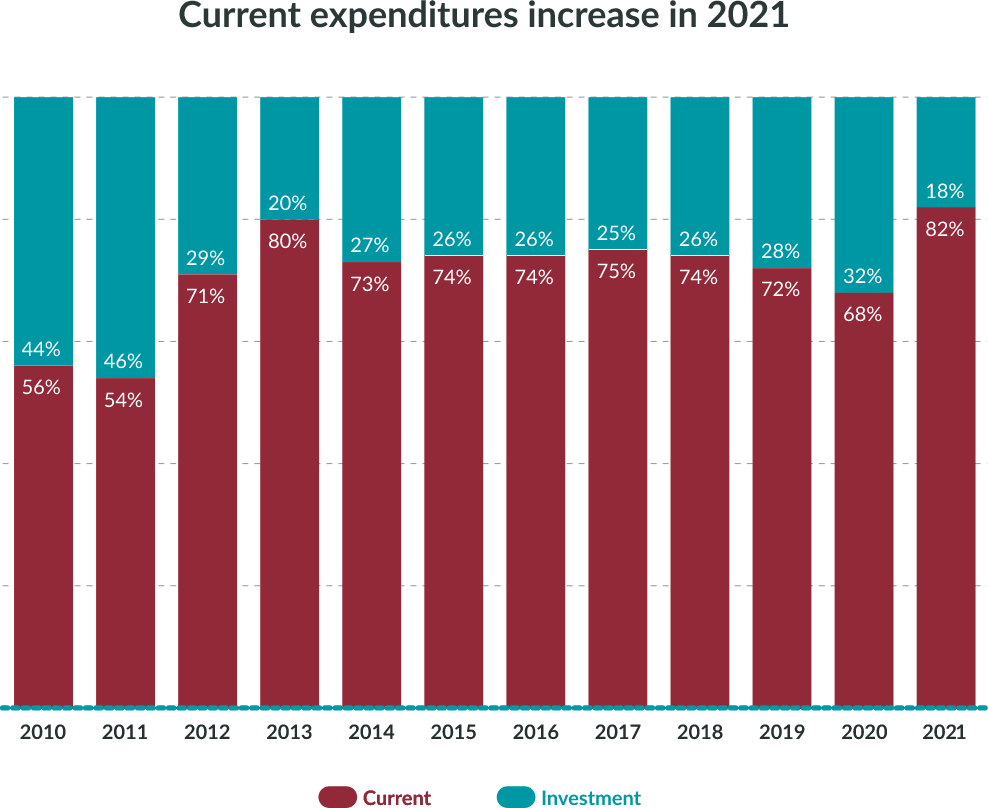

Though the 2021 budget specifics are still being debated in the People’s Council, the vast majority of spending (82 percent) will be “current spending.” Current spending mainly services social support programs, like fuel and food subsidies, and the wages of public employees, who make up about a third of the workforce (1.6 million people).

For the data, calculations, and sources, click here.

The proportion of this year’s budget dedicated to current spending is the highest in the last decade. The sudden increase also reverses a three-year trend starting in 2018, in which current expenditures were gradually decreasing. Given the depth of the economic crisis Damascus is currently undergoing, the increase in current spending is quite logical.

A recent assessment by Qassioun, a Syrian newspaper, estimated that since the beginning of 2020, the average Syrian family’s cost of living has increased by 74 percent. To have a comfortable standard of living, a Syrian family would need 700,000 Syrian pounds ($304) per month. An average public sector salary is around 55,000 Syrian pounds ($24), leaving most families unable to satisfy their basic needs.

Thus, to prevent outright famine, the government is focusing on the immediate needs of its population via social programs and subsidies. The sudden increase in current spending also signifies the end of Damascus’s ambitions to cash in on reconstruction projects—at least for the near future.

In 2018, the Syrian government began to focus on reconstruction projects for the first time as it regained control of large swathes of southern Syria and made inroads against the opposition-held enclave in the northwest. With Bashar al-Assad’s victory seemingly just a matter of time, international investors began to quietly discuss who would be able to cash in on the sizable contracts required to rebuild the country.

Though Damascus put aside some cash for reconstruction funding over the last few years, it was mostly counting on foreign investments to finance the bulk of reconstruction projects. The cost of rebuilding physical assets damaged during the war is at least $117 billion, according to the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) in 2020. It would take Syria over 1,700 years to pay that sum, based on the amount it invested in reconstruction in 2020 ($66 million).

The passage of the Caesar Act sanctions package by the United States in December 2019 largely dashed these hopes for foreign funding. The fear of secondary sanctions seems to have warded off most international investors—save a few Russian and Iranian companies.

Without outside funds, Damascus simply does not have the capacity to engage in any wide-scale reconstruction. Its economic situation is continuing to worsen and the government will have to dig deep to cover the basic needs of those living under its control.

The 2021 budget indicates that Damascus will occupy itself with ensuring the minimum standards of living for its population—no easy task given the economic crisis gripping the country. Medium-to-large size reconstruction projects will be put on hold. Unless a political settlement is reached and the sanctions are lifted to enable reconstruction, the economy of regime-held Syria will continue to struggle.