Contents

Executive Summary

Introduction

I. A Brief History of China-Syria Relations (1949-2010)

II. China and the Syrian Conflict: Balancing Threats and Opportunities

- Beijing’s Vetoes on UNSC Syria Policy

- Brothers in Arms? China’s Military Role and Security Interests in Syria

- Jihadi Erasmus in Syria: China’s Uyghur Problem

- China’s Soft-Power Toolkit in Syria: Trade and Aid

- China’s Vaccine Diplomacy in Syria

III. The Belt and Road Initiative and Syria: Investments and Reconstruction Projects

Conclusion

Executive Summary

Over the past decade, China’s engagement in the Syrian conflict has received relatively little coverage. This is partly due to Beijing’s intent to take a backseat role in order to avoid jeopardizing its long-term objectives in the region. In doing so, China has instead played a more proactive role behind the scenes, allowing it to fully leverage its political and economic influence to its favor. This study provides a detailed overview of China’s overall involvement, interests, and foreign policy objectives within the Syrian crisis.

Since 2011, Beijing has advocated (on paper at least) for a political solution to the conflict while shunning direct involvement. Instead, Chinese engagement within the Syrian arena has occurred through a number of lenses, most notably through its diplomatic engagement in the UN Security Council. However, while China has largely remained adherent to its non-interventionist foreign policy with respect to the Syrian conflict, it has continued to build on its ties with the al-Assads, which date back to the 1960s when Hafez was then the Minister of Defence.

From a security perspective, Beijing’s concerns have stemmed primarily from the influx of Uyghur fighters, from China’s troubled western province of Xinjiang and from Central Asia, into Syria. This has been a major driver behind its decision to side with Damascus.

Economically, China’s interests are less clearly defined. While it has long held minor stakes in Syria’s oil sector, the war and its subsequent economic fallout have all but wiped out its investments. However, as Western sanctions continue to hit its already decimated economy, Syria remains very much in need of affordable Chinese goods and products. This has set the stage for potential Chinese economic leverage in a market that is desperate for investment opportunities.

Furthermore, Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) touts itself as a grand geostrategic plan for the future by creating a transit network for both goods and passengers. For this initiative to be executed properly, China wants enhanced access to the Mediterranean, something Syria could provide in exchange for infrastructure and reconstruction projects.

Indeed, Beijing’s renowned experience in providing infrastructure needs to developing states provides it with a competitive advantage over the regime’s other main allies. However, while Chinese officials have gone on record supporting reconstruction and investment projects in Syria, much of it remains up in the air.

For now, Syria’s strategic and security significance far outweigh its economic importance for China—facets often lumped together by analysts. In order for Beijing to invest meaningfully in Syria, the conflict needs to provide suitable conditions for it to do so, starting with a durable political solution and the cessation of hostilities.

Introduction

In recent years, China’s role in the Middle East has been a subject of heated debate. Beijing, alongside Moscow, has taken an active role in filling the void left by the gradual withdrawal of the United States from the region over the past decade. In comparison to Russia, however, China’s position, objectives, and approach to key issues in the Middle East have mostly been overestimated by analysts and policymakers alike. More importantly, how these factors could eventually affect Beijing’s role in shaping regional stability has too often remained unaddressed. This is particularly true regarding the Syrian conflict.

China’s role in the conflict has historically received little attention, despite its active role behind the scenes. The People’s Republic of China (PRC ) has long thrived to achieve a multipolar world order in the Middle East, one in which non-interference and partnership with states in the region is a key credential. Syria’s ongoing conflict provided the perfect opportunity as Beijing seeks to implement its increasingly ambitious foreign policy.

This study takes a detailed look at China’s overall involvement and objectives within the Syrian conflict. In doing so, it argues that while Beijing’s role has helped to preserve the Syrian regime—mainly through its diplomatic backing in the United Nations (UN) and its Security Council (UNSC)—its role has taken a back seat compared with Iran and Russia. For China, this approach has served a dual purpose:

- It allowed Beijing to remain in line with the non-interventionist doctrine which has dominated China’s foreign policy since the 1970s.

- It reduced the danger of Beijing being sucked into a regional conflict, which could potentially hamper its long-term objectives in the region.

We further argue that while China’s economic interests in Syria are overestimated, they do play a significant role in Beijing’s foreign policy calculations.

This work is divided into three sections. The first offers a historical overview of Sino-Syrian bilateral relations from the establishment of diplomatic ties in the mid-1950s until the first decade of Bashar al-Assad’s rule (2000-2010). The second section dissects Beijing’s involvement in the Syrian conflict through five main lenses:

- Diplomatic engagement through the UNSC

- Arms sales and military involvement

- Security concerns stemming from foreign fighters

- Trade and aid

- Vaccine diplomacy during the COVID-19 pandemic

The third and final section discusses the prospects of reconstruction through Beijing’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

I. A Brief History of China-Syria Relations (1949-2010)

The strategic relationship between Syria and the People’s Republic of China dates back to the post-WWII era. Syria was one of the first countries in the Middle East to recognize the Chinese Communist Party’s rule over China in 1956. Simultaneously, Beijing adopted a supportive stance toward Syria’s growing tensions with Turkey and Israel, both of whom were US allies. At that time, Washington feared Syria becoming a Communist State as China improved its ties with Damascus to counter any potential “imperialist” aggression.

Following the Ba’athist coup d’etat in 1963, bilateral ties between Syria and China cooled as Damascus began to foster deeper relations with the Soviet Union (USSR). Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao visited Damascus in June 1965 on an official state visit and held talks with the Syrian head of state, Amin al-Hafiz. However, the USSR’s considerable influence over Damascus at that time effectively blocked Beijing’s efforts to develop more substantive ties with Syria.

But Syrian authorities became increasingly frustrated with the USSR’s meddling in their domestic affairs following the 1966 inter-Ba’athist coup, particularly after Moscow refused to greenlight substantial weapons sales to Damascus. In a calculated response designed to antagonize the Soviets, Syria dispatched a military delegation to Beijing led by Syria’s Chief of Staff, Lieutenant General Mustafa Tlass. General Tlass even posed for a photo-op with Mao Zedong’s little red book at a time when ideological divergence between China and the USSR was at an all-time high. Fearing that Damascus would break out of the Soviet orbit, Moscow backed down, allowing Syria to purchase the necessary military hardware.

Relations between Syria and China did not develop substantially during this period and were confined to occasional arms sales (allowed by the USSR) and superficial political support in the international arena.

As the Cold War drew to a close in 1991, much of the Middle East had become heavily dependent on US military might. Damascus attempted to counterbalance Washington’s influence in the region by fostering deeper military ties with Russia, North Korea, and China. During Syria’s limited economic openness in the 1990s, Beijing assisted Damascus in actualizing its economic reform policies. In May 1999, a Friendship Association between the Syrian Parliament and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference was founded to advance bilateral cooperation between the states.

However, the relationship between Syria and China did not truly begin to flourish until the succession of Bashar al-Assad to power in 2000. Different regional and international events forced Assad to rediscover China as a useful ally to the regime, such as the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and Syria’s covert support and training of militants to fight US forces in Iraq, as well as Rafiq al-Harriri’s assassination in 2005 and the subsequent diplomatic isolation of Damascus.

In 2004, Bashar al-Assad paid an official state visit to Beijing and met with Chinese Premier Hu Jintao, who had previously visited Damascus in 2001 as vice president. Both sides backed the creation of the Syrian-Chinese Business Council. During the meeting, Chinese officials outlined the development of Sino-Syrian relations with a focus on three major areas:

- The bilateral promotion and political engagement of both countries, including parliamentary representatives, high-level officials, and members of the Syrian Ba’ath Party and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

- The expansion of economic and trade ties, including bolstered cooperation in the fields of science, agriculture, communications, technology, and petroleum.

- The spheres of culture, tourism, health, and education.

These three policy areas formed China’s approach to Syria during much of Bashar al-Assad’s early years in office, seeing Syria as a reliable partner in a volatile region.

The subsequent deregulation of Syria’s banking sector helped deepen the economic cooperation between both states. This attracted the interest of heavyweight Chinese companies such as Huawei Technologies and Haier Group. Huawei even held a regional conference in 2007. Meanwhile, China’s automobile industry recorded 10,000 vehicle sales in Syria during the first decade of Bashar al-Assad’s rule.

II. China and the Syrian Conflict: Balancing Threats and Opportunities

The outbreak of the Syrian conflict presented China with a new set of challenges, forcing it to recalibrate its broader Middle East foreign policy in the wake of the Arab Spring. Beijing’s objectives in the conflict are a geostrategic mixture of security concerns and economic opportunities. As Syrian government forces began to regain territories previously held by Islamic State (ISIS) and rebel forces, China became increasingly wary that battle-hardened Uyghur and Central Asian fighters would gravitate toward neighboring Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan, where it would be easier to target Chinese home soil. The presence of Uyghur fighters in Syria is considered one of several drivers behind Beijing’s intensifying crackdown on Muslims in its Xinjiang province, which started in 2017. From China’s perspective, the current Syrian regime is a far better alternative to the potential chaos created by Western intervention, not least due to its historical ties with the regime and enhanced cooperation on counterterrorism issues.

Unlike most other countries, China has maintained its diplomatic presence in Damascus. Its continued relationship with the Syrian regime is part and parcel of China’s “non-interference” policy—not allowing any particular domestic choices by a foreign government to get in the way of an otherwise practical relationship. Using its diplomatic leverage, China has promoted attempts to resolve the crisis through dialogue, instead of the coercive military actions and sanctions often prescribed by the West. China has long advocated a negotiated political settlement to the war, but it has largely avoided active involvement in the conflict in order to avoid potential entanglement in regional power rivalries. Instead, as part of its flagship Belt and Road Initiative (discussed in detail later) and with the blessing of Damascus, Beijing has kept Syria’s economic potential in sight as part of its key China-Central Asia-West Asia corridor, given Syria’s underutilized coastline with the Mediterranean.

Beijing’s economic interests in Syria can also be viewed through the lens of reconstruction. China has on multiple occasions voiced its interest in contributing to Syria’s rebuilding process. However, it appears that much of those efforts have been limited to rhetoric and small-scale projects amid continued cautious monitoring of the situation on the ground. In order for China to ramp up reconstruction investment to a larger scale, it needs a feasible political solution to the conflict—something which remains unresolved.

By shielding the Assad regime, China has managed to consolidate its ties with Tehran and Moscow without having to invest substantial resources. Beijing’s siding with Damascus is also tied to its objective of countering Western influence in the region (i.e., that of the United States). This has been particularly evident with regard to foreign interventions in a state’s internal affairs. China remains wary of such actions, as it could potentially establish a precedent to be turned against itself in the future.

China’s Syria strategy has also allowed it to essentially co-opt Damascus, prompting the Syrian regime to fall in line with some of China’s own key national security issues. For example, during Beijing’s crackdown on Hong Kong in 2020, Damascus stood firmly on the side of its ally. Syria has also backed China’s strict security laws in Hong Kong, and viewed the protests as interference by the United States in the internal affairs of the PRC. Damascus’ then-deputy Foreign Minister, Faisal Mikdad, stated:

We recognize the One-China Principle and we fully support the efforts of the Chinese government to protect the interests and security of the Chinese people and of China as a country.

Unsurprisingly, Syria’s regime has also sided with China with respect to Taiwan. Damascus has on numerous occasions voiced its commitment to Beijing’s ‘One-China’ principle.

In August 2018, China’s former Ambassador to Syria, Qi Qianjin, published an op-ed in the Syrian regime’s daily newspaper Al-Watan. In it, he highlighted the strong bilateral relations between Damascus and Beijing and praised regime forces for strengthening and stabilizing the situation within the country. He also praised Syria’s efforts in deepening its relations with China by stating:

We highly commend the Syrian “Eastward” strategy and intend to cooperate more with Syria in the political, military, economic, and social fields, to actively participate in Syria’s economic reconstruction…

Throughout the past decade, China has attempted to maintain its prestige as a responsible actor in a volatile region. Nowhere has this been more visible than in Syria. In doing so, China has increasingly become an important actor within the Syrian conflict, albeit at arm’s length through its non-interventionist approach. From its perspective, Beijing has successfully managed to safeguard its regional and international interests by utilizing the international stage, particularly the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), to its favor.

A. Beijing’s Vetoes on UNSC Syria Policy

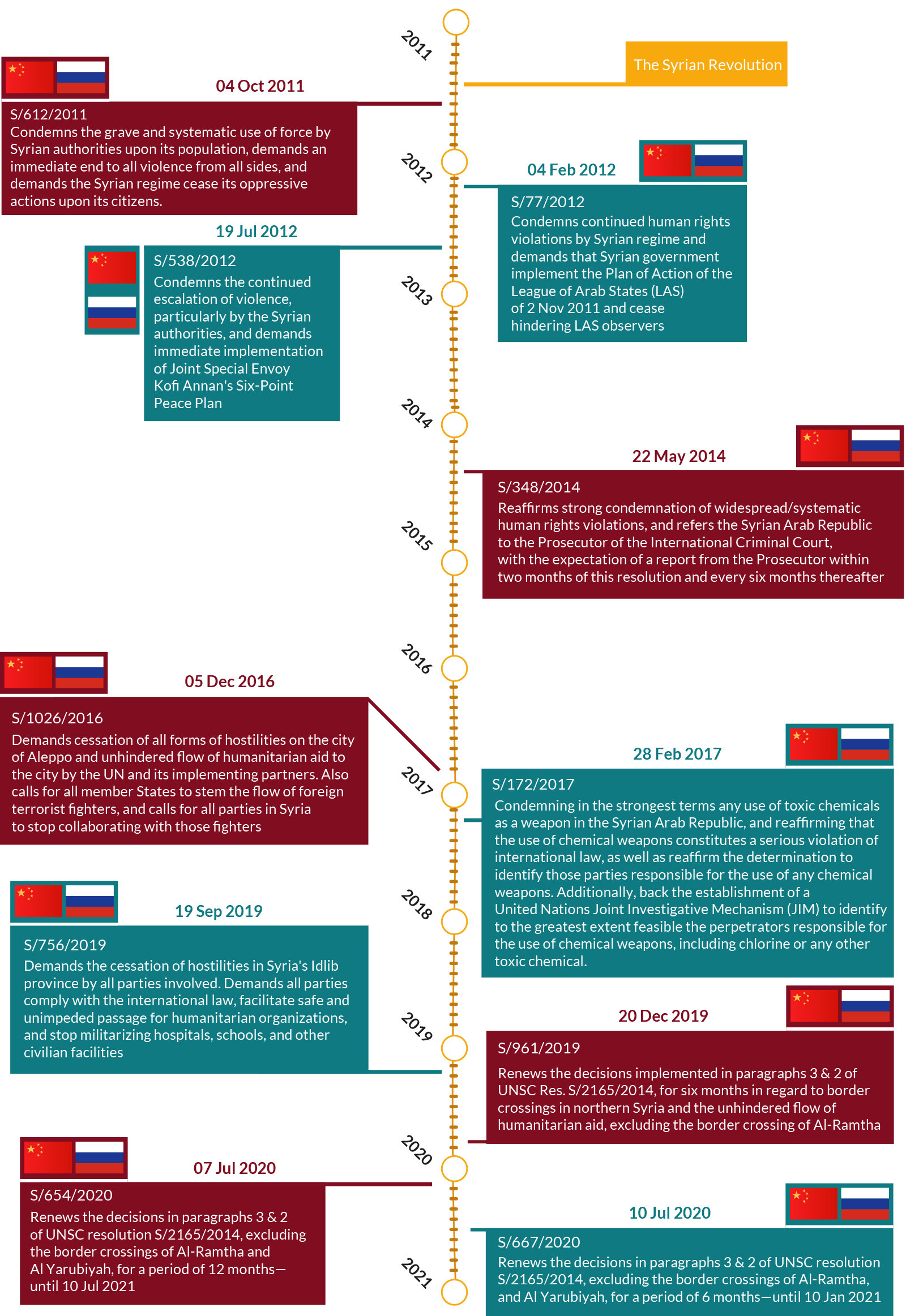

The references used in this infographic can be found in the footnotes.

As touched upon earlier, China’s non-interventionist approach in the domestic affairs of other states has been a cornerstone of its foreign policy. This has been reflected by its vetoes within the UNSC, of which Beijing is a permanent member. Similar to Russia, China’s views toward the UN’s Responsibility to Protect (R2P) policy has been directly influenced by the fallout from the Libyan crisis.

In 2011, China hesitantly abstained from voting in the UNSC on resolution 1973, which authorized military action against the regime of Muammar al-Ghaddafi. From Beijing’s perspective, the NATO-backed intervention had less to do with protecting civilians and more with providing a legal cover to overthrow Ghaddafi’s regime. This was seen as a dangerous precedent by Chinese officials, as such a pretext could potentially be used against any government attempting to deal with domestic unrest, including China itself. The ensuing Libyan carnage only reaffirmed Beijing’s perceptions, causing it to double down on its non-intervention-based approach within the UNSC.

Since then, China has sought to protect its own domestic security and avoid endorsing R2P resolutions that could jeopardize its interests abroad. This strategic approach forged a convergence of Sino-Russian policies on a number of key issues in the Middle East, specifically issues relating to territorial integrity, sovereignty, and security in the region. Since the outbreak of the Arab Spring, Beijing and Moscow have formed a unified voting bloc within the UNSC; they follow a similar voting pattern and have joint-vetoed numerous resolutions, most prominently on Syria.

The first joint veto came just months after NATO’s intervention in Libya, against a resolution drafted by nine states—including the US—which would have condemned the Syrian regime’s brutal crackdown on civilian protesters. The wording had been watered down to avert any possible veto, yet Russia and China vetoed it anyway. The second joint veto came less than a year later on 4 February 2012, on a resolution which would have adopted the Arab League’s call for President Assad to step down from office and cease violence against the Syrian opposition. Since then, China has taken concrete measures to preserve the Assad regime diplomatically, as well as a more prudent approach against R2Ps in general.

It is important to mention that Beijing has not always followed Moscow’s lead within the UNSC. It has abstained on numerous occasions [1] , favoring economic engagement to further its political involvement and to refrain from being dragged into the geopolitical dynamics of the conflict. Beijing favored UNSC Resolutions 2042 and 2043, which addressed Kofi Annan’s six-point plan authorizing the deployment of international observers to monitor the proposed ceasefire. China also backed Resolution 2118, addressing the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian conflict.

As of March 2021, China has vetoed a total of ten UNSC resolutions on Syria, compared with Russia’s sixteen. While Beijing’s use of its veto privilege is significantly less than that of Moscow’s, it is still remarkable. Prior to the Syrian conflict, China had vetoed only six resolutions in total since taking up its UN seat in 1971, marking a significant shift in its diplomatic approach.

China’s bold posture in international affairs can also be attributed to its increasing political and economic influence, particularly in the Middle East. Beijing has stepped up its engagement in the region following the publication of two main government whitepapers: The Vision for Maritime Cooperation Under the Belt and Road Initiative in 2015 and China’s Arab Policy Paper in 2016. Both documents are particularly interesting, as they focus almost exclusively on economic cooperation and refrain from heavy emphasis on issues relating to security cooperation. Beijing is careful to avoid replicating what it sees as Western-style intervention; it prefers to promote itself as a neutral partner with all countries—including countries at odds with each other—thereby emphasizing mutually beneficial agreements. This has allowed China to effectively co-opt Arab states by forcing them to refrain from criticizing its domestic and international policies or lose out on lucrative economic opportunities.

For example, following China’s UNSC veto on Syria in February 2012, Saudi Arabia sharply criticized Beijing for its shielding of the Assad regime. Since then, Arab countries have strategically refrained from condemning China on the world stage. This is depicted by the fact that no Arab state has publicly criticized Beijing’s systematic detention of Uyghur Muslim communities in China’s Xinjiang province. In 2019, Saudi Arabia went even further. It was among 37 signatories to a letter backing Beijing’s position: “Faced with the grave challenge of terrorism and extremism, China has undertaken a series of counterterrorism and deradicalization measures in Xinjiang.” Given that human rights organizations have grave concerns over the situation in Xinjiang, this reticence is concerning at best.

China’s position on the Syrian crisis has avoided heavy criticism within the international community due to its constructive approach toward the conflict. It has always publicly called for a political solution and has on multiple occasions offered to take part in mediation efforts between the Syrian regime and the opposition. This has reinforced its diplomatic stance, which rejects foreign intervention in the internal affairs of other states while at the same time promoting swift restoration and stability to regional conflicts within the Middle East.

Yet China’s approach of maintaining good relations with the governments of other states in the region could face a series of challenges. First, and despite the reduced volume of criticism from Middle-Eastern states, Beijing continues to face international backlash for siding with the Assad regime—mainly from the United States and Europe. Washington’s then-Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, heavily criticized Beijing and Moscow’s most recent joint veto in the UNSC on 20 December 2019. The resolution—drafted by Germany, Belgium, and Kuwait—would have extended the authorization and flow of humanitarian aid through six UN checkpoints without the formal consent of the al-Assad regime. Jurgen Hardt, a foreign policy spokesperson to Germany’s ruling Union Parties (CDU/CSU), said that the Chinese/Russian joint veto blocking the flow of humanitarian aid was “cynical and a crime against humanity.’’ Such international pressures could impact China’s standing on the world stage, potentially undermining its economic diplomacy in various regions where the West enjoys higher degrees of leverage.

Secondly, while Beijing’s cooperation with Moscow on Syria has been steady, it could nonetheless face some difficulties in the future. As China seeks to assert itself as a key player in the reconstruction of post-conflict Syria, it may become increasingly at odds with Russia. However, China recognizes the Kremlin’s interests in the country and does not, for the time being at least, appear to seek an active undermining of Moscow’s presence in the Middle East.

Finally, the presence of Chinese and Uyghur militants within the ranks of various jihadist groups on Syrian soil continues to pose a major security threat to Beijing. The movement of such groups has been a key driver for China’s support of the Assad regime.

B. Brothers in Arms? China’s Military Role and Security Interests in Syria

Prior to the war—particularly during Hafez al-Assad’s reign—Beijing played a more active role in supplying the Syrian armed forces with Chinese military expertise and weaponry. The ballistic missile capability of Damascus is one notable example.

In 1988 it was reported that China had sold 80 M-9 ballistic missiles to Syria, although the delivery was eventually canceled following diplomatic pressure from Washington. In order to avoid detection, Beijing instead opted to sell missile parts and components to Damascus. In 1996, German authorities confiscated documents that suggested Syria had purchased sensitive computer equipment from Beijing which could be used to mix chemical and biological components. Three years later, China supplied 10 tons of powdered aluminum to the Assad regime’s Syrian Scientific Studies and Research Center (SSRC), the government agency responsible for developing Syria’s chemical, biological, and ballistic missile capabilities.

Beijing’s support of Damascus continued well after Bashar al-Assad rose to power in 2000. In 2002, China proposed building a production center for SCUD missiles in Syria; it continued to rank among the top five weapons suppliers to Syria between 2006-2008. Since 2000, China is said to have sold $76 million worth of arms to Syria, although that number could be higher given the scarcity of information relating to arms sales between both countries. Beijing has also been accused of supplying chlorine gas to the Syrian regime through Iran. Gas cylinders bearing the chemical symbol for chlorine, along with the name of Chinese arms manufacturer Norinco, were reportedly found during an attack on Kafr Zita in 2014. China has since denied the allegations, but has stated that it would launch an internal investigation based on the reports. China is also said to have delivered 500 “Red Arrow-73D’’ anti-tank missiles in 2014, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s database.

More recently, there has been speculation about the potential interest of Damascus in upgrading its air defense missile systems. Following a string of Israeli airstrikes on Syrian and Iranian military installations during the course of the conflict, Chinese media outlets have suggested that Beijing could potentially offer its FD-2000 long-range missile system to Damascus in order to complement Syria’s outdated Russian-made S-300 and Pantsir-1 air defense systems.

In August 2016, Rear Admiral Guan Youfei of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), director of the Office for International Military Cooperation in China’s Military Commission, was appointed to Syria for the military training of regime forces. During the same month, Guan headed a delegation to Syria and met with then-Defense Minister Fahd Jassem al-Freij in Damascus. The meeting made Youfei the most senior Chinese military figure to visit the country since the outbreak of the conflict in 2011. Guan expressed his willingness to expand military cooperation between China and Syria and to increase military assistance. Chinese military advisors are reportedly already in Syria to train their Syrian counterparts on a wide range of weapons purchased from China, including rocket launchers, machine guns, and sniper rifles. A regime source highlighted the increased Sino-Syrian cooperation in recent times by stating, “There are weapons and technical supplies … the Chinese Embassy’s security delegation has been expanded, suggesting preparations for a wider role, and a Chinese team of experts had arrived in Damascus’s military airport.”

It was also reported that China’s elite special forces, the Night Tigers, had been deployed and stationed in the Syrian port city of Tartus in 2017, although this claim has not been verified. Allegedly, a 5,000-man counterterrorism unit was sent to Syria in order to combat Uyghur militants who have joined a variety of rebel groups. Both countries have enjoyed a steady stream of intelligence-sharing to counter extremist groups, some of whom include Chinese Muslims and ethnic Uyghurs. Indeed, the presence of Uyghur and Chinese militants in Syria has been a key factor for Beijing’s backing of the Assad regime.

C. Jihadi Erasmus in Syria: China’s Uyghur Problem

Much of Beijing’s security concerns have historically stemmed from the potential threat of external violent extremist groups originating from countries such as Afghanistan and Pakistan. However, with the outbreak of the Syrian conflict and its subsequent transformation into a regional conflict, China’s perceived threats have expanded significantly in geographical scope. The war in Syria attracted thousands of foreign fighters, many of whom originated from Central post-communist states in Beijing’s own backyard.

These foreign fighters have also included a substantial share of Uyghurs—the Chinese Muslim ethnic group which constitutes the largest ethnic group in China’s resource-rich province of Xinjiang. It is thought that some 5,000 Uyghur militant jihadists from Central Asia and China have flocked to Syria, joining groups such as ISIS, the Turkistan Islamic Party in Syria (TIP), and allied factions of al-Nusra Front, although the exact number remains unknown. In July 2018, China’s special envoy to Syria, Ambassador Xie Xiaoyan, stated, “I’ve seen all sorts of figures—some say 1,000 or 2,000; 2,000 or 3,000; 4,000 or 5,000; and some say even more.” Syria’s Ambassador to China appears to have confirmed the 4,000-5,000 figure. These groups pose a direct security threat for China—in 2016, a Uyghur suicide bomber targeted the Chinese Embassy in Kyrgyzstan. The attack was said to have been planned and executed by TIP and financed by al-Nusra Front.

Idlib, the last rebel-held bastion in Syria, has become a safe haven for many Uyghur militants and their families, particularly in the strategic townships of Jisr al-Shughur, Ariha, and Jabal al-Zawiya. The majority of Chinese foreign fighters have joined al-Qaeda-affiliated groups due to historic ties developed in Afghanistan and Pakistan between Osama bin Laden’s group and the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM) and its Syrian offshoot, TIP. The links between the movements are perhaps best portrayed by Abu Omar al-Turkistani. Born in Xinjiang, al-Turkistani rose through the ranks of numerous jihadist groups affiliated with al-Qaeda, having fought in the Tora Bora battle against US forces in Afghanistan as part of the Islamic Jihad Union before moving to Syria in mid-2015. Once there, he took up leading positions with al-Nusra Front and TIP. In January 2017, he was killed by a US drone strike in Idlib governorate alongside other high-ranking al-Qaeda officials—much to the appeasement of Beijing, with numerous Chinese media outlets hailing his death as a “superb New Year’s gift.” In contrast, ISIS is said to have had only around 300 Chinese militants within its ranks, according to Beijing’s state-run Global Times newspaper.

In 2016, al-Nusra Front officially rebranded itself to Hayet Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—effectively splitting from al-Qaeda. But this had no impact on its relationship with predominantly Uyghur groups such as TIP and Katibet al Ghurba al Turkistani (KGT), who continue to collaborate with HTS on the battlefield.

There have also been reports of TIP and KGT fighters receiving military training from Malhama Tactical, a for-profit mercenary group nicknamed the “Blackwater of Jihad,” which is composed of jihadist veterans from the post-Soviet orbit, and Russia’s Muslim republics of Chechnya, Dagestan, and Tatarstan. Mahalma Tactical is also said to have recruited and trained Uyghur and Han Chinese militants within its ranks and has voiced its intent to expand into China’s Xinjiang province. It aims to “shape and train angry Uyghur youth into elite fighters,” thereby threatening not only Beijing’s national security and land corridors but also the prospects of its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative.

Many Uyghurs and would-be militants have traveled to Syria through Turkey, which has historically held a supportive stance toward their cause. Ankara has taken in about 45,000 Uyghur refugees and until recently has been one of the few Muslim majority states to openly call out Beijing for its forced detention of Uyghurs in what it calls “re-education camps.” There have been speculations regarding to what extent Ankara has facilitated the presence of Uyghur militants in Syria, although these claims have not been sufficiently backed by hard evidence.

During the early stages of the Syrian conflict, China accused Turkey of turning a blind eye to TIP’s buildup in neighboring Idlib. Many Chinese analysts have suggested that Uyghur fighters have acted as a Turkish proxy as part of the grand anti-Assad coalition in Syria. Turkish nationals are also said to have supplied Uyghurs with illegal Turkish passports in order to facilitate their emigration from China. Some Uyghurs have confessed that they were bound for Syria as well as Afghanistan and Pakistan, while others did indeed settle down in Turkey after seeking political asylum in the country.

In recent years, however, Ankara’s support for Uyghur separatism has waned. Following the failed coup attempt of 2016, an increasingly isolated Turkey opted to recalibrate its foreign policy priorities. The growing distrust between Ankara and the West forced Turkey to curry favors with Beijing in order to accommodate the latter’s core interests in the region. China has also attempted to leverage its economic standing through arms sales and large-scale investments, perhaps as one means to soften Turkey’s stance on the Uyghur issue. Last year, Turkey ratified its 2017 extradition treaty with China, amidst accusations that Ankara had agreed to hand over Uyghur Muslims in exchange for COVID-19 vaccines.

As is the case with Moscow, Beijing follows a “One-Way Ticket” approach to the issue of foreign fighters from the Xinjiang and Central Asia regions—that is, they would rather see the majority of their foreign fighters killed in combat instead of captured or repatriated, which could pose a potential security threat to their respective domestic audiences.

However, most Uyghur militants intend to stay in Syria for the time being; they have moved to Syria with their families and do not plan on returning home. For them, the risks associated with their home countries and provinces are simply too high, particularly those who migrated from China. One Syrian rebel stated, “Their journey was very costly. [A Uyghur] fighter told me he sold his house to afford the trip here with his family members. How could he think of returning?” As ties between China and Turkey continue to improve, it remains highly unlikely that Ankara will allow Uyghur militants to reside in its territories should Idlib fall into the hands of the Assad regime in the future.

D. China’s Soft-Power Toolkit in Syria: Trade and Aid

Three Chinese public companies were involved in Syria’s oil sector prior to the 2011 uprising. The first and oldest is the Chinese National Petroleum Company (CNPC), which entered the market in 1977 and operated through joint ventures with Syrian state companies al-Furat and Syria-Sino al-Kawakeb. Combined, the two companies extracted nearly 104,000 barrels per day (bpd) as of 2010, with CNPC responsible for nearly a third of that. Al-Furat used to operate more than 35 fields including al-Taym, al-Omar, al-Ward, and al-Tanak in the Euphrates Valley. These oil fields were substantially damaged during international coalition strikes against ISIS in 2015 and 2016. The fields of al-Taym and al-Ward are currently under the control of the Syrian regime, while other major fields are under the control of the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces.

The operating licenses for all of those fields have or will expire between 2018 and 2024, and Russian companies have recently showed interest in investing in them.

The second Chinese company is Sinopec, which operated under a joint venture with Oudeh Petroleum in Tishrine, and with the Sheikh Mansour Oil Fields in Al-Hasakah. The venture, which started operating in 2008, was producing nearly 20,000 bpd in 2010, with Sinopec’s share at 50%.

The third Chinese company involved in the oil sector was Sinochem, which operated primarily in the Yousefieh oil field under a joint venture with Dijla Company starting in 2003. Dijla Company extracted 24,000 bpd in 2010, with Sinochem’s share at 50%.

Overall, we estimate that Chinese companies were responsible for extracting nearly 12% of Syrian oil production in 2010—46,380 of the total 385,000 bpd. Sinopec’s and Sinochem’s Syrian contracts are unlikely to have ended, and they may wish to resume operations as the situation calms. Given the tendency of the Syrian government to diversify the interests of oil companies in the country, further Chinese investments are likely to sprout again as the security situation improves.

One of the potential investments in this sector might be the long-anticipated Abu Khashab oil refinery in Dayr az Zawr, which was intensely negotiated between the Syrian government and CNPC in 2009 but never became an official agreement for unknown reasons. The refinery was planned to increase the country’s refining capacity by nearly 30%.

Along with the oil sector issues, other economic shortfalls are in play. Syria’s overall imports fell from $22.4 billion in 2010 to just $6.5 billion in 2019, according to data reported by its trading partners. The country’s exports were harmed to a much greater extent, falling from $12.6 billion to $0.7 billion, most significantly from the cessation of oil exports [2] .

To the see the interactive visualization, click here.

While Syria’s imports fell significantly after the uprising, not all of its trade partners were equally affected—in fact, because of the increasing economic integration between Turkey and opposition-held Syria in the north, Syria’s Turkish imports have increased over the course of the war. Chinese imports have fallen, but by less than Syria’s other major sources of imports (other than Turkey). This is primarily due to the competitive nature of Chinese products, especially as the purchasing power of Syrian citizens has declined [3].

To the see the interactive visualization, click here.

To the see the interactive visualization, click here.

To propel economic growth prior to the conflict, the highest share of imports from China were machinery and transport equipment. During the conflict, the highest share became manufactured products, reflecting the sharp decline in Syria’s production capacity and the pace of economic slowdown. These two interactive visualizations outline the changes in the composition of Syria’s imports from China over time.

To the see the interactive visualization, click here.

To the see the interactive visualization, click here.

Since 2011, Beijing has focused its Middle East strategy primarily on economically low-risk investments in sectors where it deems itself to have a comparative advantage to Iran and Russia—the main allies of Damascus. In doing so, China hopes to build a more positive sentiment toward its role in the conflict, which it can leverage in its favor.

One notable sector is Syria’s automobile industry, where Beijing has developed significant interest. Chinese brands such as Geely and Changan partnered with Mallouk & Company and its car manufacturing plant in Homs to begin assembling a variety of models for Syria’s domestic car market, which has been left in tatters due in part to Western sanctions. Other brands such as the Chinese Brilliance sedan have been in great demand by middle-income households, due to their reliability and low maintenance costs.

Apart from trade and investments, China has also provided some humanitarian support to the Syrian government through bilateral and multilateral channels, but it is a fringe provider, in particular compared with the United States and Germany. Since 2017, Beijing has unilaterally committed only 310 million yuan ($46 million) total in humanitarian aid; it has made some additional donations through numerous UN governmental agencies and multilateral organizations such as the World Food Program (WFP), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

In 2016, China signed an agreement with the WFP to provide $2 million in humanitarian assistance to Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon, which was completed in 2018. Beijing also delivered 1,000 tons of rice to the Syrian port city of Latakia in 2017 as part of its relief package under the BRI.

A series of direct Chinese grants have also been provided to the Syrian government. In 2020, both sides signed an agreement under the framework of economic, scientific, and economic cooperation which included a $14 million handout—the fifth of its kind, with the total amount of grants reaching $60 million—to assist with Syria’s humanitarian needs.

E. China’s Vaccine Diplomacy in Syria

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has posed a serious public health crisis in Syria and overwhelmed its already battered healthcare system. Cases have been steadily on the rise throughout the country, particularly in rebel-held Idlib as well as in the SDF-held northeast. While official case numbers provided by the Syrian regime are over 16,000 as of March 2021, the real number is estimated to be over 40,000 nationwide. This comes at a time when Damascus has been subjected to a series of economic sanctions and a plummeting currency, which has severely restricted its capabilities in effectively countering the pandemic. Furthermore, the regime’s main backers—Iran and Russia—have both been harshly impacted by COVID-19. In December 2020, Tehran’s coronavirus-related death toll surpassed 50,000 while Moscow’s surpassed 186,000, forcing both countries to prioritize their domestic response to the pandemic.

In contrast, China has successfully managed to contain the pandemic. Beijing is also the only major economy to have recorded economic growth in 2020, with its economy expanding by 2.3% over the course of the previous year. As a result, China began to shift its focus to the manufacture and global distribution of vaccines. The Middle East, in particular, has become a crucial market for Beijing’s “Vaccine Diplomacy,” with countries including the UAE, Bahrain, Jordan, and Egypt all authorizing the Chinese Sinopharm vaccine. During the early stages of the pandemic, China also sent medical equipment, PPE supplies, and doctors to the region in an effort to combat the virus and change public perceptions regarding its origins—that it is not a “Chinese Virus’’ as claimed by the former US Trump administration.

Beijing has also provided medical assistance to Syria throughout the past year. In April 2020, China donated 2,016 COVID-19 test kits to Syria. In the same month, Beijing sent another shipment of medical aid, which included face masks, infrared thermometers, goggles, and protective suits; these were presented by the Chinese Embassy in Damascus. China has also made use of multilateral organizations in Syria to assist Syrian authorities in combating the pandemic. In January 2021, China delivered a major shipment of medical equipment to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) in Damascus in an effort to assist Palestinian refugees in the war-torn country.

In terms of vaccination, Syria is reportedly set to receive the first batch of COVID-19 vaccines in April 2021 from China and Russia through the COVAX platform of the World Health Organization (WHO). The initial batch is said to cover the needs of only about 20% of the Syrian population. Syrian Foreign Minister Faisal Mikdad has expressed Damascus’ hope that it would receive the Russian vaccine for free. However, if that is not the case, Syrian authorities may very well be inclined to seek other economically viable alternatives, with China’s Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines being one option.

Indeed, in early February 2021, Beijing announced that it would send a batch of 150,000 doses as aid to Syria, although no clear timeline was provided for this shipment. Furthermore, large-scale bilateral agreements between these states are yet to be signed.

III. The Belt and Road Initiative and Syria: Investments and Reconstruction Projects

China’s Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road Initiative, Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) for short, purports itself to be a grand geostrategic plan for the future, with a massive $900 billion investment in transforming ancient trade routes, including the historic Silk Road, into a 21st-century transit network for both goods and passengers. Eleven (at last count) separate corridors will crisscross both land and sea to weave the Far East, Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and potentially Europe into a vast multi-continent trade web with China as the main center. The initiative focuses on a wide range of areas that include trade and investment projects, cultural exchanges, policy coordination, the connectivity of facilities, and the financial integration of member states.

The BRI is currently more of a vision: a list of loosely-connected ideas with little in the way of homogenous results, as would be expected with 93 countries currently signed on but without standardized parameters for projects. More importantly, it’s worthy of note that the BRI is not a grant-in-aid project; rather, it intends to work primarily through concessionary financing offered to member states. As described by Prabir De, Professor at the Research and Information System for Developing Countries in New Delhi, the BRI “is a series of loans and not a basket of free lunches.” But the idea is appealing, especially to developing countries who cannot secure funding from other sources for infrastructure projects.

This is precisely where Syria fits into the equation. The ongoing conflict has caused widespread havoc and destruction to its urban infrastructure and left its economy in shambles. The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia (ESCWA) estimated in 2020 that Syria’s economic losses exceed $442 billion, with at least $117.7 billion in destroyed physical assets. This is a hefty bill to foot for any developed country, let alone for Syria, whose financial system and economy continue to be plagued by bad governance and corruption. While Syria’s overall lack of natural resources may have limited its economic partnership with China in the past, the ongoing conflict has brought important infrastructure needs which Beijing may be poised to invest in. With damaging Western sanctions in place, and little financial and expertise competition from Iran or Russia, China has an unprecedented ingress into an underdeveloped economy with no direction to go but up as the war draws to a close.

In 2019, President Assad highlighted that the regime’s main international backers would be in a pole position to access Syria’s lucrative reconstruction projects, stating that “friendly countries like China, Russia, and Iran, will have priority in this rebuilding.” While Beijing is aware that both Moscow and Tehran have more political and military leverage over Damascus due to their active involvement in the Syrian conflict, the economic advantage remains firmly in favor of China.

The combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and the crippling effect of US sanctions has severely deteriorated Iran’s economy, potentially limiting its capability to foot a big chunk of Syria’s reconstruction bill. The ramifications of its economic fallout are predicted to continue well into the foreseeable future, with Iran’s GDP now estimated to contract at least 4.5% in 2020/2021. Similarly, Russian state coffers are likely to remain depleted as the country battles a deep recession and continues to grapple with the consequences of the pandemic amid a record number of cases in late 2020.

Additionally, it’s important to note that both Russia and Iran are less “capable” of reconstructing Syria as their companies tend to be primarily experienced in the oil sector. Syria needs efficient electricity-generating plants, construction, food processing plants, production machinery, etc. These are areas where, in contrast to Moscow or Tehran, Chinese companies have a renowned competitive advantage in meeting the crucial infrastructure needs of developing states, as seen in Africa.

Damascus’s geostrategic access to the Mediterranean Sea is an appealing incentive for China’s BRI ambitions. For Beijing, the Levant [5] is an important component of the BRI’s China-Central Asia-West Asia economic corridor that would reduce China’s reliance on the Suez Canal in an attempt to diversify its trade routes. Indeed, Syria’s Mediterranean seaports of Latakia and Tartus might be feasible options for China’s telecommunications and infrastructure projects, which aim to connect the Chinese mainland with Eurasia. China has also expressed its interest in reconstructing the Tripoli-Homs railway network, allowing them to service Lebanon’s Tripoli port which is set to become the main transshipment hub of the Eastern Mediterranean.

As the Syrian conflict staggers to a long drawn-out close, arguably in favor of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, the country is set to become an important component of China’s foreign policy in the Levant. The recent meeting between senior Syrian and Chinese officials symbolizes China’s growing recognition of Syria’s budding national reconstruction effort and the potential for China to play a leading economic role in Syria’s future. China has on multiple occasions voiced its willingness to help out in financing Syria’s reconstruction as part of its BRI.

In 2017, Beijing hosted the First Trade Fair on Syrian Reconstruction Projects and pledged its intention to invest $2 billion to assist in establishing industrial parks. In the same year, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi stated, “The international community should attach importance to and actively support the reconstruction of Syria,” adding that “China will also make its own efforts to this end.” Additionally, more than 200 Chinese companies attended the 60th Damascus International Trade Fair in 2018, signing a variety of trade deals ranging from building trades to steel plants. President Xi Jinping also announced in 2018 that China would be providing $20 billion in loans and $106 million in financial aid to Middle Eastern states. While the exact amount allocated for Syria remains unknown, it is said that only $90 million has been set aside for Yemen, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria combined.

Syrian officials have also expressed their interest in cooperation within the BRI framework. In response to Syria’s invitation to the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in April 2019, Syria’s Presidential Media Advisor, Buthaina Shaaban, said, “The Silk Road is not a silk road if it does not pass through Syria, Iraq, and Iran.”

However, while Chinese officials have gone on record in support for reconstruction and investment projects, virtually nothing has materialized on the ground so far. Beijing is seemingly wary of risks associated with investing capital in Syria so long as the security condition in the country remains highly fragile and a political solution appears far off. The lingering threat of foreign interventions, either from Turkey or the United States, and the recent tightening of US sanctions are likely to continue to deter large-scale investments, at least for the time being. It seems that the majority of China’s announcements have been confined to sensationalist headlines and photo-ops without actually transpiring into concrete initiatives. Regime forces have yet to regain control of the remaining third of the country, much of which is resource-rich—as in the northeast—and will be essential in paying off any large-scale loans. The stabilization of Syria and the potential end to the conflict through a sustainable political solution will almost certainly turn Syria into a regional priority for Beijing. This would allow economic ties to grow, which in turn would assist with the long-term stability of the region as a whole and advance China’s geostrategic interests.

Conclusion

Throughout the past decade, China has attempted to take a more active role in the Middle East. This has not always been easy, as it was forced to navigate through a region which has become a battlefield for competing international forces in the wake of the Arab Spring. Beijing has attempted a delicate balancing act by advancing its geostrategic interests while at the same time remaining in line with its non-interventionist foreign policy. Its role in Syria has characterized precisely that.

During the decade of Syria’s conflict, China has intentionally taken a backseat role while leveraging its position as a leading actor on the international stage in terms of global diplomacy. This has allowed it to maintain good ties with all of the conflict’s main stakeholders, particularly Turkey, Iran, and Russia. With regard to the Syrian regime, Beijing has focused on common interests by offering assistance in combating terrorism as the threat of Uyghur militants continues to loom large. In addition, China (alongside Russia) has effectively shielded Damascus in the UNSC, thereby countering Western influence in the region—a common objective for both sides.

China will also be a natural and indispensable partner in Syria’s post-conflict reconstruction, given its long experience in the field and its involvement in infrastructure. But as its Belt and Road Initiative begins to take shape in the region, China may find itself at a crossroads which could force it to revisit its non-interventionist policy. Any large-scale project in a highly volatile region like the Middle East puts its economic interests at direct risk. For now, the risk of intervening in regional conflicts, such as in Syria, could impact Beijing’s interests more than the risk of abstaining. Furthermore, though unlikely at the moment, China’s partnership with Russia could potentially be tested in the future as both countries begin to compete for infrastructure development projects.

It’s also important to note that China’s deepening engagement in Syria is primarily dependent on US actions in the conflict and not the opposite. So long as Washington’s Syria policy remains inconsistent, Beijing will attempt to fill the void left by successive US administrations by taking a more central economic role, not just in the Levant, but also in the broader Middle East. For the time being, Syria’s strategic and security significance far outweighs its economic importance for China—issues often lumped together by analysts. In order for China to invest meaningfully in Syria, the conflict needs to provide it with suitable conditions for doing so, starting with a durable political solution and the cessation of hostilities.

https://undocs.org/en/S/2011/612

https://undocs.org/en/S/2012/77

https://undocs.org/en/S/2012/538

https://undocs.org/en/S/2014/348

https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2016/1026

https://undocs.org/en/S/2017/172

https://undocs.org/en/S/2019/756

https://undocs.org/en/S/2019/961

https://undocs.org/en/S/2020/654

https://undocs.org/en/S/2020/667

[1] China has abstained on UNSC resolutions related to Syria on at least six occasions at the time of writing. For a full list of UNSC vetoes, please see https://research.un.org/en/docs/sc/quick/veto

[2] The data comes from the Standard International Trade Classification System, United Nations COMTRADE. Note that the data has its own quality issues; for example, COMTRADE does not include data reported from Iran.

[3] Note that the figures stated in this study refer to trade only with mainland China—excluding Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan.

[4] Note that Syria’s exports are above zero. Hover over the lines in the chart to see the exact value.

[5] From Britannica.com, a historical term referring to “the countries along the eastern Mediterranean shores…associated with trading ventures… The name Levant States was given to the French Mandate of Syria and Lebanon after World War I, and the term is sometimes still used for those two countries…”