Nicholas Lyall, Karam Shaar

The pace of military action in Syria has plateaued. With the assumption of a frozen conflict comes the attendant assumption that humanitarian conditions are also likely to be stable. This could not be further from the truth.

While the level of violence has declined relatively over the past couple of years, this was more than offset by a number of other negative factors, causing a significant deterioration in humanitarian conditions.

Starting in late 2019, Syria in general, and regime-held areas in particular, were hit by a crippling combination of economic shocks. This included the banking crisis in Lebanon (late 2019), the COVID-19 pandemic (early 2020), the U.S. Caesar Act sanctions (passed in late 2019, but taking effect in July 2020), and finally the feud between Bashar al-Assad and his cousin, tycoon Rami Makhlouf (starting from late 2019), which caused significant ambiguity in the business environment, curbing economic activity.

Humanitarian conditions continue to deteriorate, driven by three factors, and urgent action is now needed to avoid a famine.

Factor 1) The severity of the current drought

Syria is currently in the midst of one of the worst droughts in recent memory. The Syrian agriculture minister described it as the worst in seven decades.[1] While the European Commission offered a less dire description — referring to it as the worst drought Syria has suffered in 25 years —[2] the state of affairs is undoubtedly dire, with the head of the Union of Agricultural Specialists in the Autonomous Administration of Raqqa warning that Syria’s northeast, the country’s breadbasket, is facing “real catastrophe.”[3]

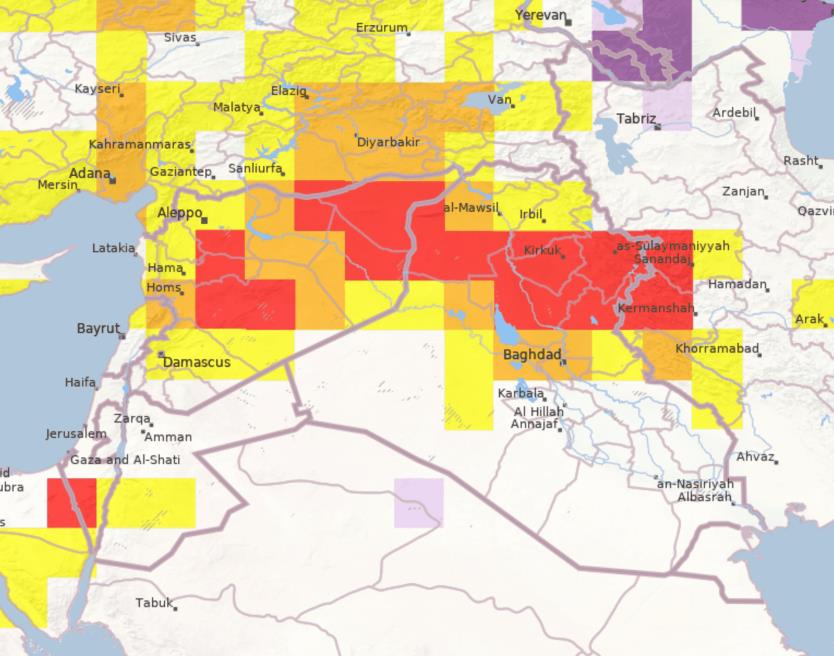

The data aptly illustrates the agricultural catastrophe facing Syria. Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI)[4] data for October 2020 to March 2021 (the wet season) shows that essentially all of the country suffered drier-than-normal conditions, with the prime wheat-producing regions of the northeast suffering vastly drier conditions than usual. In other words, Syria’s key agricultural regions saw far less rainfall than normal in the months in which they would normally receive almost all their rainfall.[5]

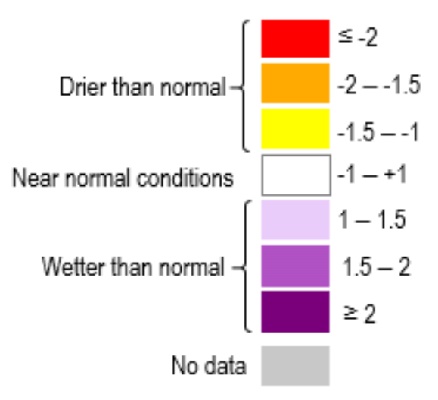

In addition to cereals biomass, overall vegetation biomass is also disappearing. The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) for Syria’s northeast is showing significantly negative levels of vegetation health and density. Similarly, much of the country’s northwest — also a key agricultural region, home to fruit trees (including pistachio and olives) and producing melon and watermelon, early vegetables, barley, wheat, corn, and sugar beet –[9] is also suffering negative vegetation health.

- Firstly, only 16-17% of Syria’s planted land is irrigated according to the latest data.[11] Compounding this is the ongoing fuel crisis, which is reducing the capacity to run wells using diesel fuel, meaning the extent of irrigated land is also decreasing.[12]

- Secondly, the Euphrates supplies the irrigated lands with water, and the amount of water flowing down through the river has lessened as Turkey has also suffered from several poor rainfall seasons.[13]

- Thirdly, this naturally decreasing flow of water down the Euphrates is being compounded by ongoing investment in dams by Turkey along the waterway. Turkey’s three largest dams now sit along the Euphrates, and as these are used to siphon off more and more water as the dams become increasingly central to Turkey’s energy production,[14] the amount of water reaching northeastern Syria is significantly decreasing.

Accordingly, not only is Syria’s irrigated land a small percentage of its cultivable land, but it is being further jeopardized by the declining water flow through the Euphrates. We are already clearly seeing the effects of this lesser flow. For instance, at Syria’s Tabqa Dam, near Raqqa, water levels as of June 2021 were at 20% of their normal level.[15] It is important to note that the impact extends far beyond irrigated land — 60% of Syria’s water resources originate from Turkey,[16] so the decreased Euphrates flow is directly threatening the accessibility of drinking water for Syrians nationwide.

The agricultural misgovernance that was practiced throughout the rule of the Assads — sustained overgrazing caused desertification, and groundwater reserves were overused and depleted —[17] since the 1960s has meant Syria’s agriculture has lost its resilience to water scarcity. Accordingly, droughts like the current one now pose a far greater danger of agricultural collapse.

The ability of Syria to feed itself is fast disappearing, and this is evident in spiraling food insecurity across the country.

Factor 2) Unprecedented food insecurity

As laid out above, Syria’s ability to feed itself is set to continue to decline precipitously. However, the starting point for this decline is already dismal, as the Syrian population has never been this vulnerable. According to a World Food Programme (WFP) statement, about 12.4 million people (nearly 60% of the population) are now food insecure and do not know where their next meal will come from: “This is the highest number recorded in the history of Syria, with an increase of 57 percent since 2019.”[18] Of this 12.4 million, 1.3 million are already severely food insecure.[19]

Moreover, even before the drought, things have been getting steadily worse in the past few years, with the nationwide average cost of a standard reference food basket increasing month on month between August 2019 and May 2021, only changing trajectory in May due to the official devaluation of the Syrian pound the month before.[20] The severity of the situation is highlighted by two key statistics: firstly, the national average of food prices increased by more than 200% from mid-2020 to mid-2021,[21] and secondly, there was a 61% rise in the number of households that reported poor or borderline food consumption from May 2020 to May 2021.[22]

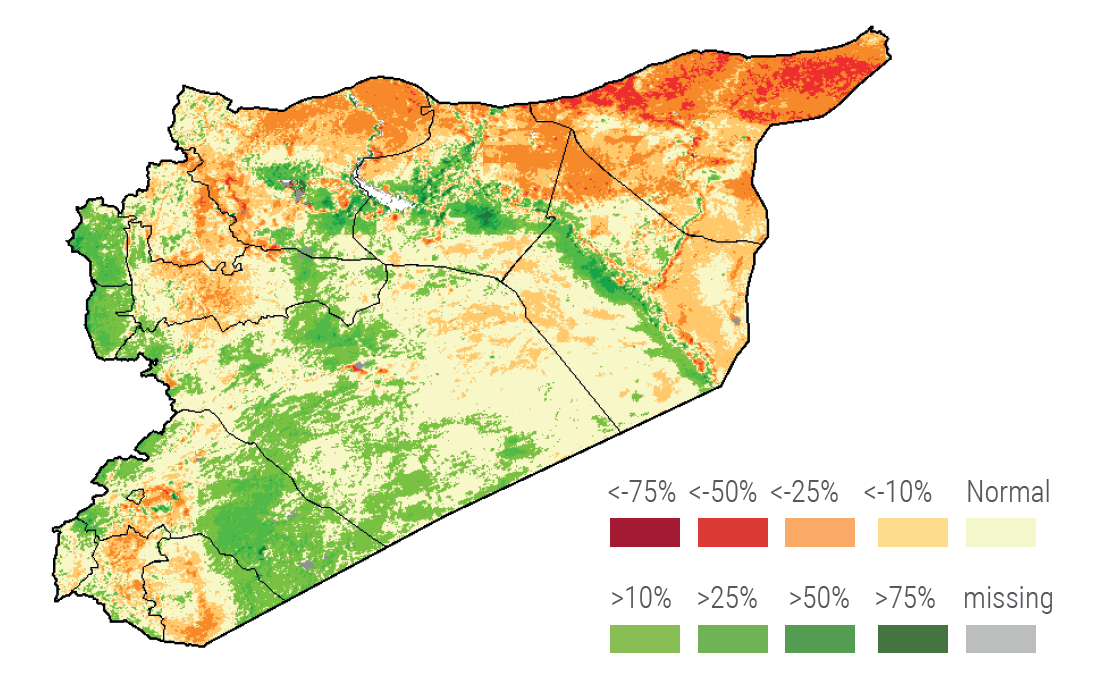

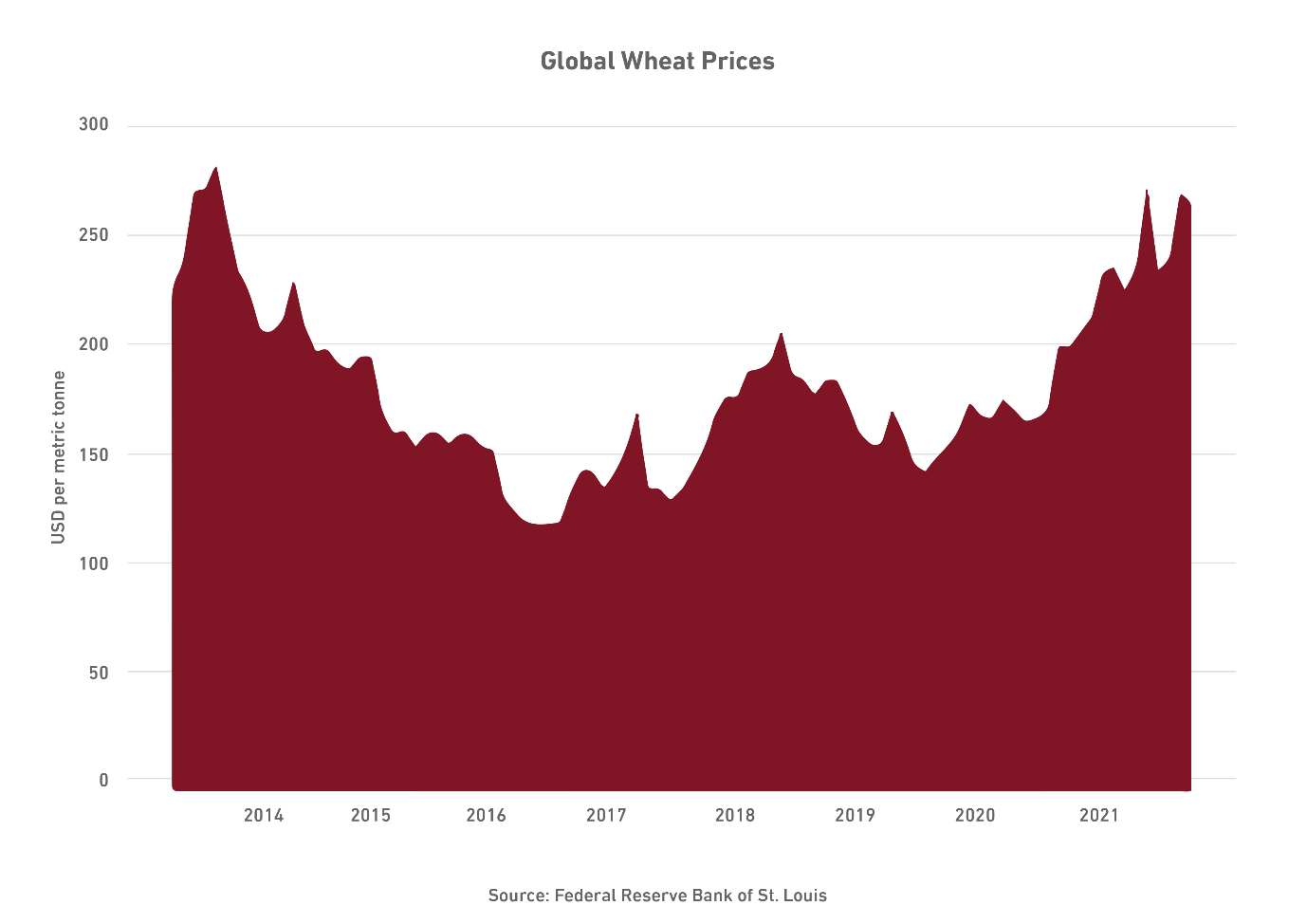

Given Syria’s dwindling agricultural production, could it import the food it so desperately needs? Unfortunately, this is highly unlikely as Syria’s foreign currency reserves are almost non-existent. Even Russia, Syria’s closest partner along with Iran, has not come anywhere close to fulfilling the deal it signed with Damascus to export 1.5 million tons of wheat to the country by the end of 2021 due to Syria’s lack of funds.[23] As shown in Figure 3, global food prices have hit the highest level in over a decade, rising by more than 30% in the last year according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).[24] A drastic increase in the price of wheat over the past year, as shown in Figure 4, has been a large driver of this. Accordingly, it is inconceivable that Syria will be able to afford to import food, especially the wheat it so desperately needs, from other nations at market prices.

Factor 3) Declining humanitarian aid funding

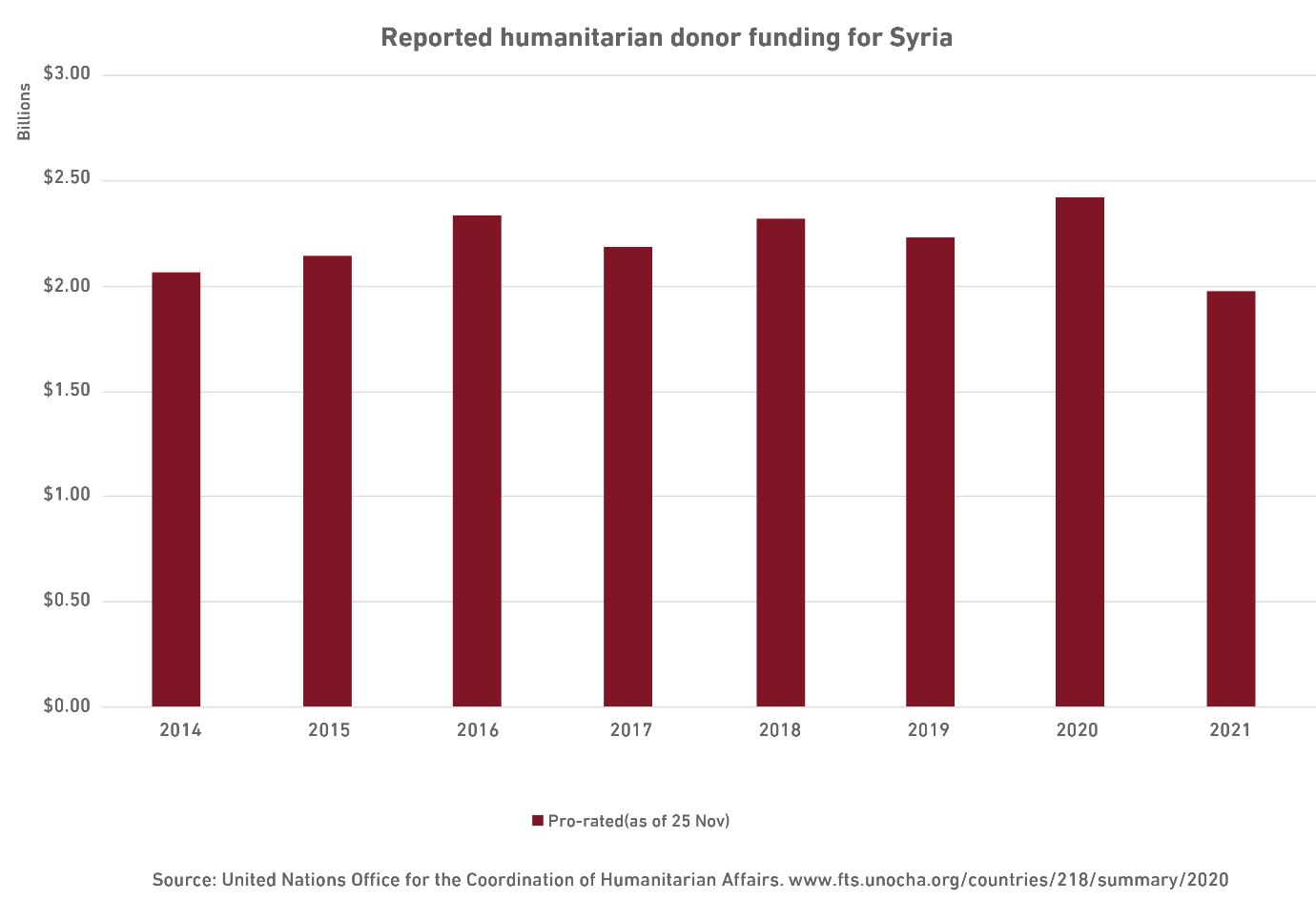

The demand for humanitarian assistance in Syria has never been greater. However, in the face of this growing demand, humanitarian funding to Syria, at least through the U.N., is actually declining. As of June 2021, merely 15% of the $4.2 billion (i.e. $0.63 billion) requested by the U.N. for Syria for the year 2021 had been delivered, as compared to $1.4 billion of the $3.8 billion (i.e. 37%) requested for 2020 by the same point that year.[28] As the figure below makes clear, despite growing needs, reported humanitarian donor funding for Syria as of Nov. 25, 2021 is at its lowest level since 2014.[29]

The imperative for donor governments

Clearly, such aid cuts are occurring at the worst possible time, when aid needs to be increased due to Syria’s rapidly declining ability to feed itself as a result of the drought. As droughts are perceived as slow-burn situations compared to humanitarian catastrophes like natural disasters, donor governments don’t seem to be aware of the extreme urgency that the humanitarian response to Syria’s drought requires. The imperative for donor governments is to immediately shift gears and transition to a proactive, pre-emptive approach regarding the coming famine in Syria as opposed to a reactive one. Humanitarian action requires significant time for planning and implementation, meaning action is required now. Waiting any longer might mean it will be too late. To avoid this impending humanitarian crisis, donor governments should focus their efforts on three fronts:

- Increase humanitarian aid to Syria to meet the minimum requested by U.N. agencies, especially the WFP.

- Ensure aid reaches affected populations and is not diverted along the way, predominantly by the Syrian regime. This includes ensuring the exchange rate applied to U.N. transfers matches that in the black market and U.N. agencies are independent from pressure by the regime.[33]

- Ensure the renewal of cross-border aid to northwest Syria, or better still, come up with a permanent alternative mechanism for delivering aid to those areas without it being influenced by the Assad regime. While other parts of Syria are not faring much better, northwest Syria is particularly vulnerable as most of the population live hand to mouth, in scattered camps, under the constant bombardment of Russian and regime planes.

1- الشامية, شبكة الدرر. (2021, May 22). موجة جفاف هي الأشد منذ سبعة عقود في سوريا. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from الدرر الشامية website: https://eldorar.com/node/163832.

2- European Commission – Joint Research Centre. (2021, April 23). GDO Analytical Report: Drought in Syria and Iraq – April 2021 – Iraq. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from ReliefWeb website: https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/gdo-analytical-report-drought-syria-and-iraq-april-2021.

3- عنب بلدي. (2021, September 8). “الإدارة الذاتية” تحذر من “كارثة” جرّاء الجفاف شمال شرقي سوريا. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from عنب بلدي website: https://www.enabbaladi.net/archives/511203.

4- SPI is a drought measurement that compares accumulated rainfall for a recent time period (e.g. March-June this year) with the long-term rainfall average for that same period throughout a historical range (e.g. March-June from 1980-2020).

5- U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2021, June 22). Syrian Arab Republic: Euphrates water crisis & drought outlook, as of 17 June 2021 – Syrian Arab Republic. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from ReliefWeb website: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syrian-arab-republic-euphrates-water-crisis-drought-outlook-17-june-2021.

6- European Commission – Joint Research Centre. (2021, April 23). GDO Analytical Report: Drought in Syria and Iraq – April 2021 – Iraq. Retrieved November 25, 2021, from ReliefWeb website: https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/gdo-analytical-report-drought-syria-and-iraq-april-2021.

7- European Commission Joint Research Centre Mars. (n.d.). Syrian Arab Republic – Anomaly Hotspots Of Agricultural Production. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from mars.jrc.ec.europa.eu website: https://mars.jrc.ec.europa.eu/asap/country.php?cntry=238.

8- al-Khalidi, S. (2021, June 21). Syrian drought puts Assad’s “year of wheat” in peril. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/syrian-drought-puts-assads-year-wheat-peril-2021-06-21/.

9- Bayram, M., & Gök, Y. (2020). The effects of the War on the Syrian Agricultural Food Industry Potential. Turkish Journal of Agriculture – Food Science and Technology, 8(7), 1448–1462. https://doi.org/10.24925/turjaf.v8i7.1448-1462.3278

10- UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2021, June 22). Syrian Arab Republic: Euphrates water crisis & drought outlook, as of 17 June 2021 – Syrian Arab Republic. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from ReliefWeb website: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syrian-arab-republic-euphrates-water-crisis-drought-outlook-17-june-2021.

11- Syrian Arab Republic Office Of Prime Minister – Central Bureau Of Statistics. (2020). 2020 Statistical Yearbook. Syrian Arab Republic Office Of Prime Minister – Central Bureau Of Statistics.

12- al-Ghazi, S. (2021). The Wheat And Bread Crisis In Syria And Its Impact On The Population. Retrieved from The Center for Middle Eastern Studies (ORSAM) website: https://www.orsam.org.tr/d_hbanaliz/the-wheat-and-bread-crisis-in-syria-and-its-impact-on-the-population.pdf.

13- UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2021, June 22). Syrian Arab Republic: Euphrates water crisis & drought outlook, as of 17 June 2021 – Syrian Arab Republic. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from ReliefWeb website: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syrian-arab-republic-euphrates-water-crisis-drought-outlook-17-june-2021.

14- Orient Policy Center. (2020). Identifying the Soft Spots in North-East Syria’s Fragile Arrangements: Water Geopolitics. Orient Policy Center.

15- UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2021, June 22). Syrian Arab Republic: Euphrates water crisis & drought outlook, as of 17 June 2021 – Syrian Arab Republic. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from ReliefWeb website: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syrian-arab-republic-euphrates-water-crisis-drought-outlook-17-june-2021.

16- Karnieli, A., Shtein, A., Panov, N., Weisbrod, N., & Tal, A. (2019). Was Drought Really the Trigger Behind the Syrian Civil War in 2011? Water, 11(8), 1564. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11081564.

17- De Châtel, F. (2014). The Role of Drought and Climate Change in the Syrian Uprising: Untangling the Triggers of the Revolution. Middle Eastern Studies, 50(4), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2013.850076; Ide, T. (2018). Climate War in the Middle East? Drought, the Syrian Civil War and the State of Climate-Conflict Research. Current Climate Change Reports, 4(4), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-018-0115-0.

18- UN News. (2021, November 12). في ختام زيارة إلى سوريا، مدير برنامج الأغذية العالمي يحذر من التدابير القاسية التي يضطر الأهالي لاتخاذها بسبب الجوع والفقر. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from أخبار الأمم المتحدة website: https://news.un.org/ar/story/2021/11/1087382.

19- The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, & The World Food Programme. (2021, July 30). Hunger Hotspots: FAO-WFP early warnings on acute food insecurity (August to November 2021 outlook). Retrieved November 20, 2021, from The World Food Programme website: https://www.wfp.org/publications/hunger-hotspots-fao-wfp-early-warnings-acute-food-insecurity-august-november-2021; al-Khalidi, S. (2021, June 21). Syrian drought puts Assad’s “year of wheat” in peril. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/syrian-drought-puts-assads-year-wheat-peril-2021-06-21/.

20- World Food Programme. (2021). WFP Syria Situation Report #5 (2021). Retrieved from World Food Programme website: https://api.godocs.wfp.org/api/documents/63eb0734103a49d8a54d7a1ef1171f72/download/.

21- al-Khalidi, S. (2021, June 21). Syrian drought puts Assad’s “year of wheat” in peril. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/syrian-drought-puts-assads-year-wheat-peril-2021-06-21/.

22- World Food Programme. (2021). WFP Syria Situation Report #5 (2021). Retrieved from World Food Programme website: https://api.godocs.wfp.org/api/documents/63eb0734103a49d8a54d7a1ef1171f72/download/.

23- Devitt, P. (2021, May 28). Russia plans to supply up to 1 mln T of wheat to Syria in 2021 – Interfax. Retrieved September 25, 2021, from Nasdaq website: https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/russia-plans-to-supply-up-to-1-mln-t-of-wheat-to-syria-in-2021-interfax-2021-05-28-0; al-Khalidi, S. (2021, June 21). Syrian drought puts Assad’s “year of wheat” in peril. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/syrian-drought-puts-assads-year-wheat-peril-2021-06-21/.

24- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2021, November 4). World Food Situation – FAO Food Price Index. Retrieved November 20, 2021, from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations website: https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en/.

25- The FAO Food Price Index is a measure of the monthly change in international prices of a basket of food commodities. It consists of the average of five commodity group price indices weighted by the average export shares of each of the groups over 2014-2016.

26- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2021, November 4). World Food Situation – FAO Food Price Index. Retrieved November 20, 2021, from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations website: https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en/.

27- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. (2021). Global price of Wheat. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis website: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PWHEAMTUSDM.

28- Calculations are done using the OCHA’s Financial Tracking Services (FTS). https://fts.unocha.org/countries/218/summary/2021

29- Calculations are done using the OCHA’s Financial Tracking Services (FTS). https://fts.unocha.org/countries/218/summary/2021

30-UN News. (2021, November 12). في ختام زيارة إلى سوريا، مدير برنامج الأغذية العالمي يحذر من التدابير القاسية التي يضطر الأهالي لاتخاذها بسبب الجوع والفقر. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from أخبار الأمم المتحدة website: https://news.un.org/ar/story/2021/11/1087382

31- The Syrian Observer. (2021, September 8). WFP Reduces Humanitarian Aid Food Basket for North-western Syria. Retrieved October 16, 2021, from The Syrian Observer website: https://syrianobserver.com/news/69504/wfp-reduces-humanitarian-aid-food-basket-for-north-western-syria.html.

32- UN News. (2021, November 12). في ختام زيارة إلى سوريا، مدير برنامج الأغذية العالمي يحذر من التدابير القاسية التي يضطر الأهالي لاتخاذها بسبب الجوع والفقر. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from أخبار الأمم المتحدة website: https://news.un.org/ar/story/2021/11/1087382.

33- Hall, N. (2021, October 20). How the Assad Regime Systematically Diverts Tens of Millions in Aid. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from CSIS website: https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-assad-regime-systematically-diverts-tens-millions-aid.